Claude Shannon Beating Roulette

Claude Shannon and Ed Thorpe

Famous roulette code crackers from the sixties.

Claude Shannon and Ed Thorpe took multiple casinos to the cleaners in the sixties with their Roulette Clocker.

There have been some great minds that have devoted their time and brainpower to beating the roulette wheel, and one of the most famous is that of Claude Shannon in the sixties.

Claude Shannon

Claude Elwood Shannon (1916 – 2001) was a US mathematician, electrical engineer, and cryptographer who later became known as the Father of Information Theory without whom we would never have seen close up pictures of Jupiter, surfed the Internet or played Clash of Clans on our mobile phones.

He was a titan in the world of mathematics.

Claude Shannon and Ed Thorp claimed to be the first men to crack the roulette code using a predictive algorithm in 1960, Ed Thorp being the serial casino pest who invented card counting in Blackjack.

That’s in dispute, as these two were inspired by the exploits of Hibbs and Walford in the 1940s, but you make your own mind up!

No More Bets Please

The key to their method was the fact that you can still bet after the croupier has spun the wheel, until he or she says “No More Bets Please”. Thorp and Shannon carried out a series of experiments on their own wheel.

They successfully predicted zones into which the ball would come to a rest, with enough accuracy to give them an edge over the casino.

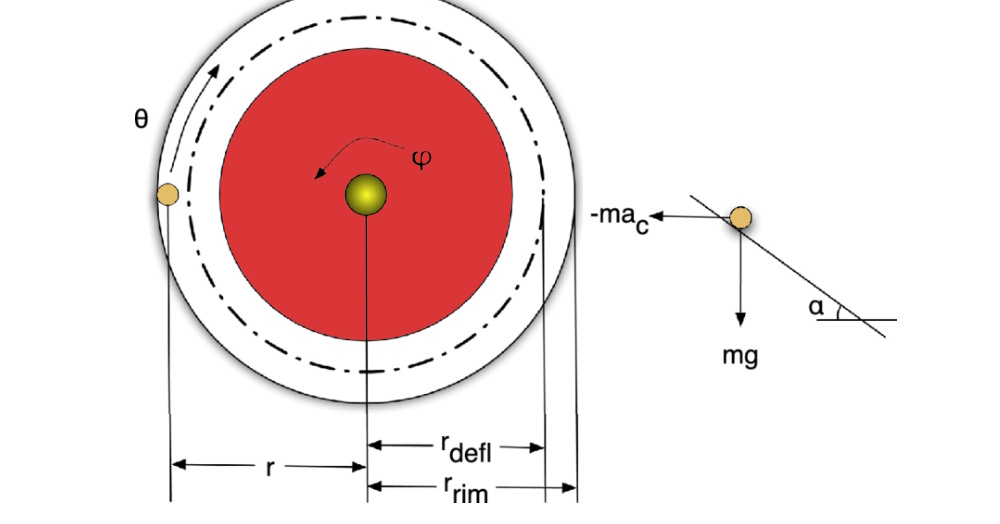

They did this by measuring the speed of the wheel’s rotation (assuming it to be constant- a pretty accurate assumption given that roulette was invented as a by-product of someone trying to build one of Pascal’s Perpetual Motion Machine), the speed of the ball and its rate of decay.

Mapping the Path of the Ball

So, they were mapping out the ball’s spiral path around the track, and plotting it against the rotation of the wheel.

Of course, there are plenty of chaotic events going on too, with the ball jumping off the diamonds on the wheel, but they found that they could at least minimise any chaotic effects on their algorithm- enough to give them a statistical edge that they could profit from when using a systematic betting strategy.

They didn’t need to win every time, just more than they lose to make this work. Just like the casino.

In fact, Ed Thorp has kindly shared some of the articles he wrote for the Gambling Times on his website.

Ed Thorp’s Gambling Times Articles:

Sensors on the Wheel

Unfortunately, the method involved a lot of kit – much of which was impossible to take into real life casinos.

The speed was measured with micro-switches built into a shoe, and the curve modelling was done with analog computing (this was the sixties remember) with radio transmitters transmitting the wheel information to a computer elsewhere (you couldn’t miniaturise this kind of computing power into a shoe in those days).

You needed a player with good hand eye coordination to measure the ball passing through certain locations to determine its speed.

You needed to nail the location of the ball to within one ball’s width and transmit the information.

This was a two man job (one measuring, the other betting).

Patience Needed

Thorp and Shannon and their wives discovered that the system required time and patience and training over time to make sure that the speed measurer in particular was on top of his or her game.

Ultimately, they became bored and moved onto other projects, but there is no doubt that these two men laid the groundwork for subsequent Roulette Clockers who have successfully cracked the roulette code with predictive algorithms.

And, of course, the technology, computing power and possibilities of hiding the technology have all improved exponentially since the 1960s. That’s Moore’s Law for you.

How it Fared in Las Vegas

Shannon and Thorpe’s exploits in Las Vegas have now become one of the legends of roulette.

Imagine carving up a roulette wheel into eight zones. By 1961, Thorp and Shannon reckoned they had a system that could accurately predict which of those zones would end up with the roulette ball.

Shannon made sure Thorp was sworn to absolute secrecy.

Ed Thorp

Do you Have a Light?

The roulette busting computer was the size of a pack of cigarettes, and manipulated by Thorp’s and Shannon’s big toes with micro-switches in their shoes.

One switch booted up the computer and the other timed the wheel and the ball. Once the wheel speed was measured, the computer sent a musical scale whose eight tones mapped the 8 quadrants passing a reference point. Both men heard the music via a small earphone in one ear.

You can see how this was a precarious situation to put yourself in, given that the men were trying to rip off casinos in the sixties that were probably run by the Mob!

The rest, as they say, is history. Luckily for Planet Earth, the men returned to devoting their time to more high-brow pursuits. And you could probably argue, that thanks to Shannon’s ground-breaking work on information theory, these two men opened up whole new box of tricks for roulette clockers to use against the casinos.

FAQs

Questions

-

What were the key challenges that Shannon and Thorp faced building their roulette clocker device?

Shannon and Thorp faced some real bumps in the road while developing their roulette prediction device:

– Technical issues: The clocker, which many say was the world’s first wearable computer, was not that reliable. The sixties wiring would short out or break when tested in the casino.

– Practical considerations: While the clocker worked well in the lab, using it in a noisy, high-adrenaline casino environment was a different ball game.

– Hardware problems: During their Las Vegas run in the summer of 1961, a small hardware issue stopped them from laying sustained big bets, despite the device predicting a 44% gain.

– Secrecy worries : The team was very nervous about being caught red-handed using the device in casinos which would have lead to apprehension and possibly even violence in those day with the mafia controlling many of the establishments.

– Complex Modelling: Predicting the ball’s behaviour became very difficult once it dropped into the chaotic second phase of its patch, bouncing off the diamond obstacles on the wheel and then the pocket dividers. Not easy!

Despite these difficulties, Shannon and Thorp gained an edge over the house with their roulette clocker and demonstrated their gift for applied mathematics in real world cases. -

What were the key innovations in Shannon and Thorp’s roulette clocker?

The wearable roulette clocker built by Claude Shannon and Edward Thorp in 1960-61 had several key clever designs:

-Miniaturization: The device was very small for its time, about the size of a pack of cigarettes with twelve transistors.

– Discreet inputs: The team used microswitches hidden in their shoes, operated with their toes to record data without looking suspicious.

– Wireless comms: The device sent info via radio waves to a miniature speaker hidden in the user’s ear.

– Real-time processing: The roulette clocker calculated predictions on the fly, with the last tone indicating the octant to bet on.

– Hiding techniques: The team painted wires to match their skin and hair colour and used gum to fox the parts to the wearer.

– The machine used a musical scale with eight tones to transmit information to the player.

This team was well ahead of its time! -

What flaws in the wheel made this possible?

– Unbalanced wheel: Even a slight tilt in the roulette wheel, (a fraction of a degree), could result in a “drop zone” where the ball would fall with more regularity from the outer rim.

– Wheel Wear: Equipment worn down from multiple spins could develop predictable patterns in ball trajectories.

– Surface irregularities: sweat from a croupier’s hand, dust or other substances could affect the ball’s path.

– Steady ball deceleration: As friction worked on the ball, its angular momentum would drop in a predictable way, allowing the team to guess with more confidence about when it would leave the wheel rim.

– Timing: By measuring the amount of time it took for the ball to complete one circuit around the wheel, they could predict with more confidence when it would hit a deflector.

– Systematic bias: later analysis of data suggested that each wheel had a unique signature that could be exploited.

– Dealer Signature. Croupiers also tended to impart systematic bias into the ball’s path.